Are buffets efficient?

I recently attended an academic conference and was struck by the inefficiency of the buffet-style dinner. The conference had approximately 500 attendees, and dinner was scheduled for 6:30 PM following a 15 minute break in the conference program. A 15 minute break is not enough time to go back to the hotel room and take a nap, and barely enough time to find a quiet corner and get some work done, but it is a perfect amount of time to crowd around the buffet waiting for dinner to open.

When dinner finally opened, all of the food was arranged on a single table, inviting the attendees to form a single line to serve themselves. As you can imagine, this line was quite long. I was lucky enough to be one of the first people through the line, but by the time I finished eating a half hour later, the line was still very long. I had been waiting for someone who was towards the middle to end of the line, and this person still had not made it through yet.

I found it odd that feeding people should be so slow. From my experiences in undergraduate dining halls, it is possible to feed more people in a shorter amount of time. A key difference between these situations is that in undergraduate dining halls, food is often served at individual stations, meaning you only need to wait in line for food you want to eat. By contrast, in the catering style, it is often served all at one table, with diners waiting in a single line and accessing the dishes one by one. I wanted to examine the efficiency of these two systems. This is important not only for minimizing the mean wait time so that everyone gets their food faster, but also for minimizing inequality between people at the front and end of the line. This ensures that everyone has the opportunity to dine together.

Model

I modeled this situation as a single line in a buffet versus individual lines for each different dish. I made the following assumptions:

- Some people may be faster or slower at serving themselves.

- Some foods can be served faster than other foods.

- People may not want all of the food which is being served, and each person wants a different random selection of foods.

- Only one person can serve themself a particular dish at one time.

- When dishes have their own individual lines, people look at the lines for the foods they want to eat and stand in the shortest line next.

- People already know what the options are and where they are located.

I calculated the wait time for each person in the simulation as the total amount of time it took a person to pass through the buffet. I then looked at the mean wait time for the group as well as the inequality in wait time for people in the group, defined as the third quartile minus the first quartile. Each simulation was run many times to ensure accurate statistics.

Number of dishes wanted

Let us suppose that not everyone wants the same number of dishes, but that all dishes are equally attractive. First we look at the case when there are a limited number of dishes.

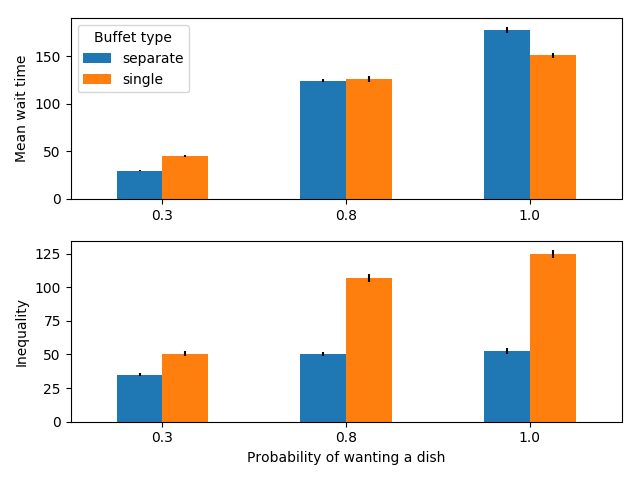

100 people serving themselves in a buffet with 6 dishes

We see that when there aren’t very many dishes and most people want all of them, it is faster to have a single line. This may be counter-intuitive, but it is due to the fact that people do not optimally distribute themselves, but instead choose the shortest line. Suppose for example that one dish is much slower to serve than all of the others. People who choose this food last will have to wait approximately the same amount of time as they would have if there was a single line and they ended up at the end, because this dish serves as the bottleneck. However, the people who are at the front of this line will still need to wait in more lines for the other dishes, because other people tried to serve themselves these dishes first. As a result, having multiple lines can sometimes increase the amount of time for the fastest people and not decrease the amount of time for the slowest people.

Additionally, there is a large inequality in wait times, i.e. some people will get through the line quickly, while others will be stuck in line for a long time. This is the case for both serving styles, but is especially pronounced for the case with multiple lines.

Let us also examine the case when there are many dishes to choose from.

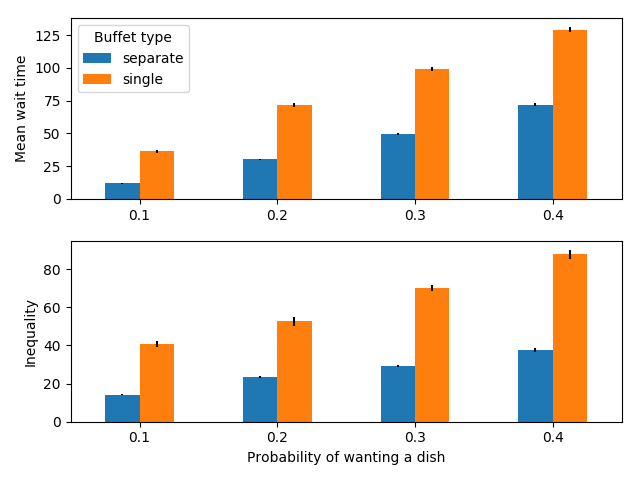

100 people serving themselves in a buffet with 20 dishes

When there are many dishes to choose from (here 20), no matter how many dishes people may want (within reason), individual lines reduce both the mean wait time and the inequality in wait times compared to a single line. Intuitively, this is because people can distribute themselves and they only have to wait for the dishes they want to eat.

Additionally, let’s look at the case when there are many people.

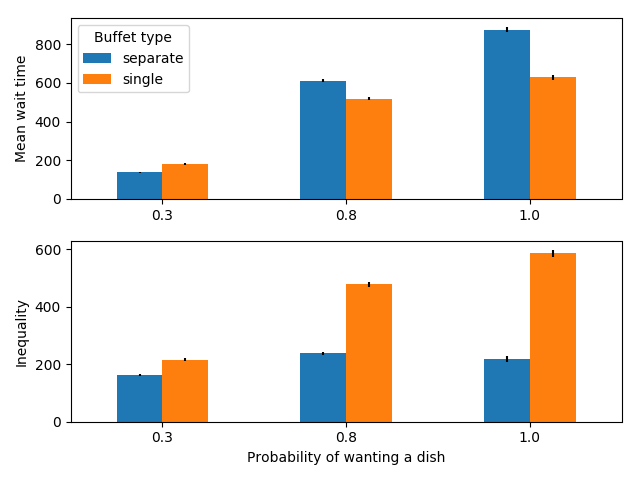

500 people serving themselves in a buffet with 6 dishes

In this case, we see the counter-intuitive result again: the mean wait time is quite a bit higher for individual lines when most people want most of the foods, however inequality is still lower.

Finally, we can examine the case when there are very few people.

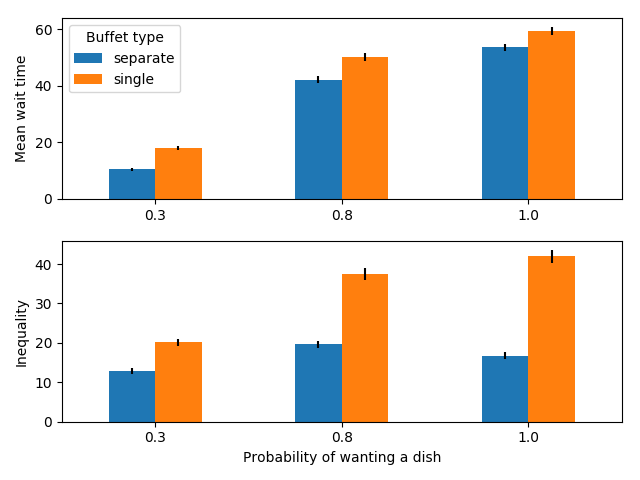

30 people serving themselves in a buffet with 6 dishes

In this case, separate lines are better for both mean wait time and equality.

Fairness

A fair system is one in which the amount of time someone waits is proportional to the number of dishes they want. In an unfair scenario, someone who only wants one dish must wait for the same amount of time as someone who wants all of the dishes.

Let’s look at whether this form of fairness holds. First, we look at how long someone must wait depending on how many dishes they want.

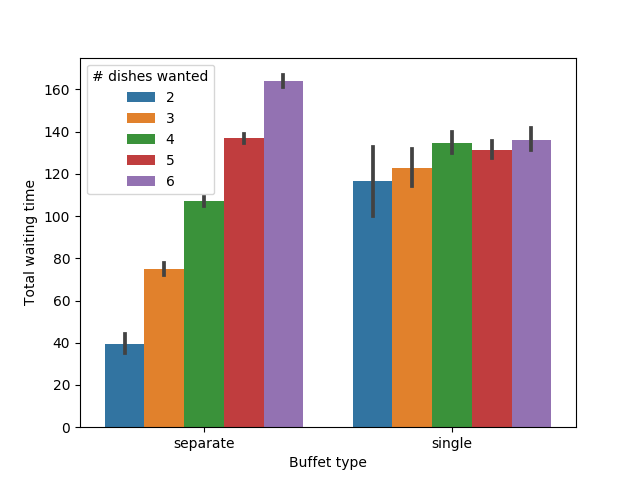

Average wait time differs depending on how many dishes a person would like

As expected, when there is only one line, everyone must wait for approximately the same amount of time, no matter how much food they want to eat. People who want all of the dishes in a line must wait for less time on average, but someone who only wants one dish must wait for a very long time. By contrast, when there are multiple lines, the amount of time people wait is proportional to the number of dishes they want to try.

Similarly, it might be fairer that someone who can serve themself quickly has a shorter waiting time than someone who is slower.

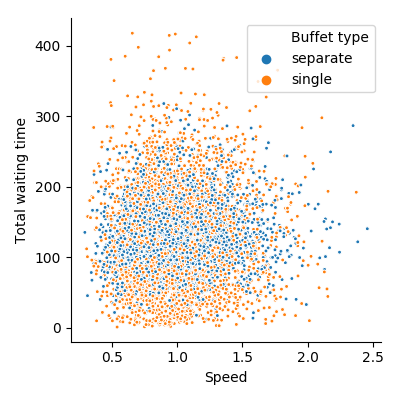

Points represent people. There is no significant correlation (\(p>.2\)) between time spent waiting and serving speed

Unfortunately this does not seem to be the case in either system. Rather, people who are slow to serve themselves take approximately the same amount of time in line as those who are fast.

Summary and conclusions

In summary, when there are a lot of people present, if everyone wants most of the food at the buffet, a single line counter-intuitively reduces the mean wait time. However, this single line substantially increases inequality in wait times, meaning that some people will have to wait for a long time while others can go through immediately. Additionally, people who only want a small amount of food must wait a long time to serve themselves. A more fair but slightly less efficient system is one where there is a separate station for each dish, but this can be inefficient when most people want most of the dishes available.

This analysis leaves out a few factors which are difficult to account for. For example, it assumes the amount of time taken to walk from one food to another is negligible, and that people know a priori what food they would like to eat and where it is located. Both of these have the potential to slow down serving times in the case with separate lines. This analysis also doesn’t account for several other factors which are important in real life. For example, it assumes that space is not an issue. It also assumes there is enough seating to accommodate everybody; if only a limited amount of seating is available, a high inequality is desirable as it prevents everyone from going to the dining area at one time.

One method which is often employed to speed up single lines is having more than one identical line, or two sides on the same line, likewise, in the case of separate lines, there are sometimes “stations” which have identical dishes. In both cases, because we assume people balance themselves by going to the shortest line, doubling the number of copies of all dishes would be expected to approximately cut the mean wait time in half.