Beyond the overtone series: the overtone grid

The overtone series, also known as the harmonic series, is one of the most fundamental explanations for what makes music sound pleasant. Whenever you hear a note played on a musical instrument, the note isn’t just made of one frequency. The tone you perceive is the base frequency (the “fundamental”). However, the note also consists of overtones, several higher pitched frequencies, which give each musical instrument its distinct sound (its “timbre”). The overtones series is the reason why thick, tightly-voiced chords sound muddy on low-pitched instruments; why the trombone needs to move its slide to play different notes; and why the V7 chord desperately wants to resolve to a I chord.

This post describes how I turned the overtone series into a grid and composed a piece of music based on it. If you just want to hear the piece, you can download the score and listen to a performance by pianist Chiara Naldi.

Reminder: the overtone series

To construct the overtone series, some fundamental frequency \(f_0\) is multiplied by whole numbers. So, the first frequency is \(1 \times f_0\), the second is \(2 \times f_0\), the third is \(3 \times f_0\), and so on:

Image of piano keys highlighting the overtone series

Another way to think about the overtone series is as the vibration of a string. Suppose we find a string of length \(L_0\) that vibrates at our fundamental frequency \(f_0\). Then, we cut the string into equal parts, so that each of the new short strings has the same length. If we cut the string in half, each string has length \(L_0/2\), and if we cut it in thirds, the lengths are \(L_0/3\), and so on. More generally, if we cut it into \(N\) equal parts, then each part has a length of:

Image of cuts of a violin string highlighting the overtone series

It turns out that a string cut into two equal parts will vibrate at the frequency \(2f_0\), three equal parts will vibrate at \(3f_0\), and \(N\) equal parts will vibrate at \(N f_0\). So, we have two equivalent ways to think about the going up the overtone series: as an even multiple of a fundamental frequency, or as a string being cut. In both of these cases, we have some number (such as 2, 3, or \(N\) in the examples above) which represents the term of the overtone series. We call these the 2nd, 3rd, or \(N\)‘th harmonics.

Generalising the overtone series

In the example above, we divided the string into \(N\) different segments, but we cut each segment to be the same size. What if, instead, we took more than one segment at a time? Now, instead of cutting at every single location where we marked, we look at all of the string lengths which could be made by performing some, but not all, of those cuts. Let’s see what notes could come out of this type of a scheme.

Image of different cuts of a violin string highlighting a generalised overtone series

So, the first two terms do not change: they are still \(L_0\) and \(L_0/2\), corresponding to frequencies \(f_0\) and \(2f_0\). However, the next term will be a bit different. In the standard overtone series, we would have \(L_0/3\), corresponding to a frequency of \(3f_0\). Here, we have two options: the same \(L_0/3\) term with a frequency of \(3f_0\), and a new term, \(2L_0/3\), corresponding to the frequency of \(1.5f_0\). If we go up one more level to \(N=4\), we get a new term as well. We have the familiar \(L_0/4\) term with frequency \(4f\) from the overtone series, and also \(2L_0/4=L_0/2\), a frequency of \(2f\). But we have another new term as well: \(3L_0/4\), with frequency \(1.33f_0\). These frequencies line up approximately with the keys of a piano:

Image of piano keys highlighting a generalised overtone series

We notice that there are two relevant numbers now: the number of pieces we divide the string into (\(N\)), and the number of those pieces we take, which we will call \(M\). According to this scheme, instead of cutting into \(1/N\) segments, we cut into segments of length \(M/N\), where \(M<N\). (This gives us a fraction, a rational number).

Since we have two numbers instead of one, it is a bit awkward to write them in a list. Instead, we can organise these pitches on a grid. Each column of the grid is \(N\), the number of segments we divide the string into, and each row is a value of \(M\), the number of consecutive segments we take before we cut.

Because this generalisation can be arranged on a grid, we obtain not only one series of pitches, but several. We can read the grid up and down, side to side, or diagonally to get lots of different series of notes. This grid forms the basis for Music of the Leaves.

Music of the Leaves

“Music of the Leaves” incorporate each row, column, and diagonal pattern from this grid into a piece of music. It does this by layering them in one note at a time. The piece starts with the first term of the series, the fundamental, and gradually layers in the different notes. When all of the notes have been added, the patterns described above emerge.

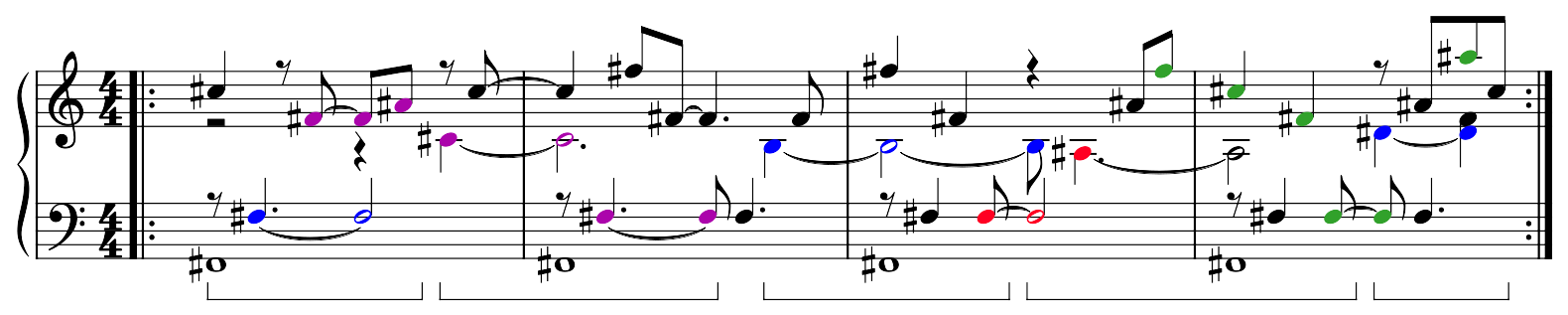

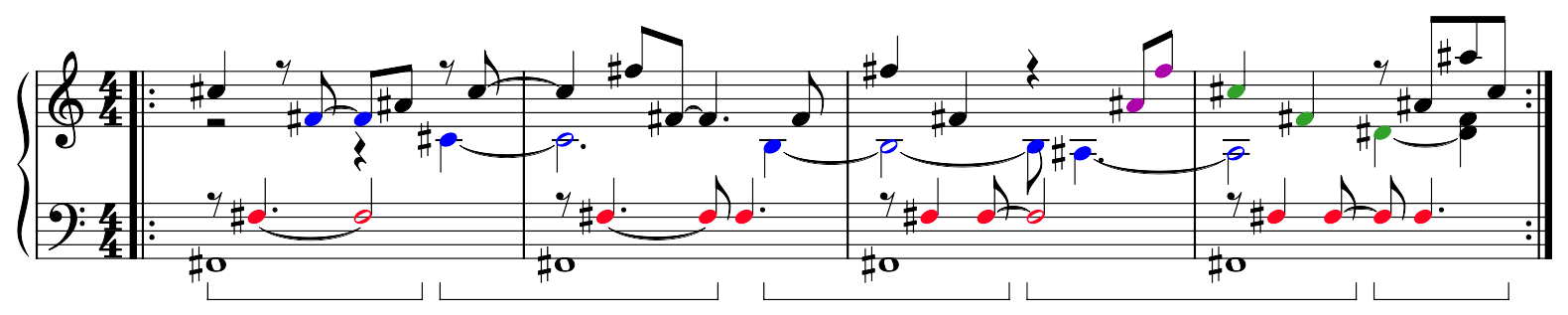

The piece is built exclusively on a repeated four-measure fragment:

Repeated four-measure passage in Music of the Leaves

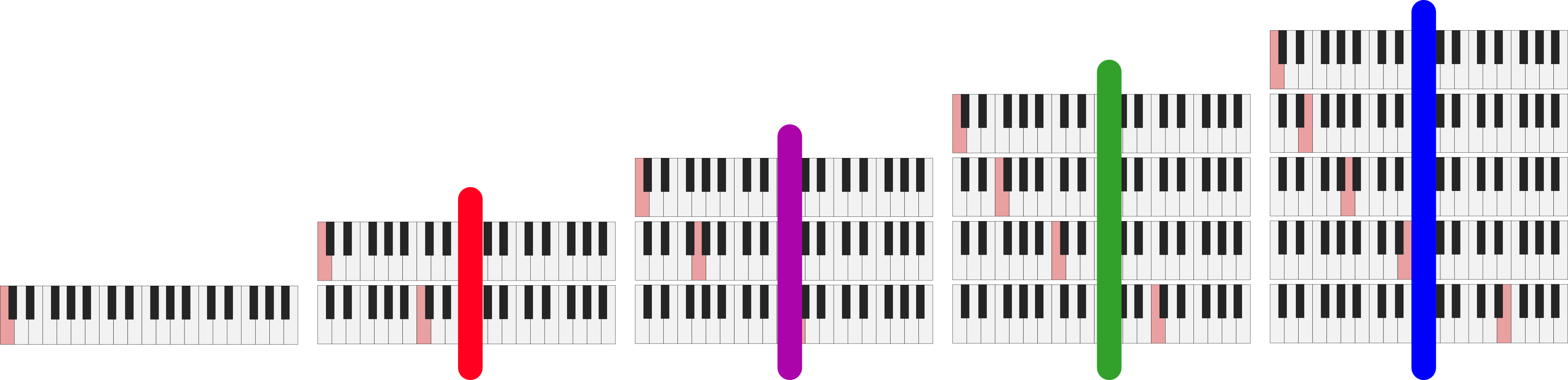

The four-measure fragment is made from patterns coming from a traversal of the grid in each direction. For instance, consider the four columns:

Traversing the overtone grid by columns

These are represented as patterns in this four-measure segment here:

Notes corresponding to the columns of the overtone grid

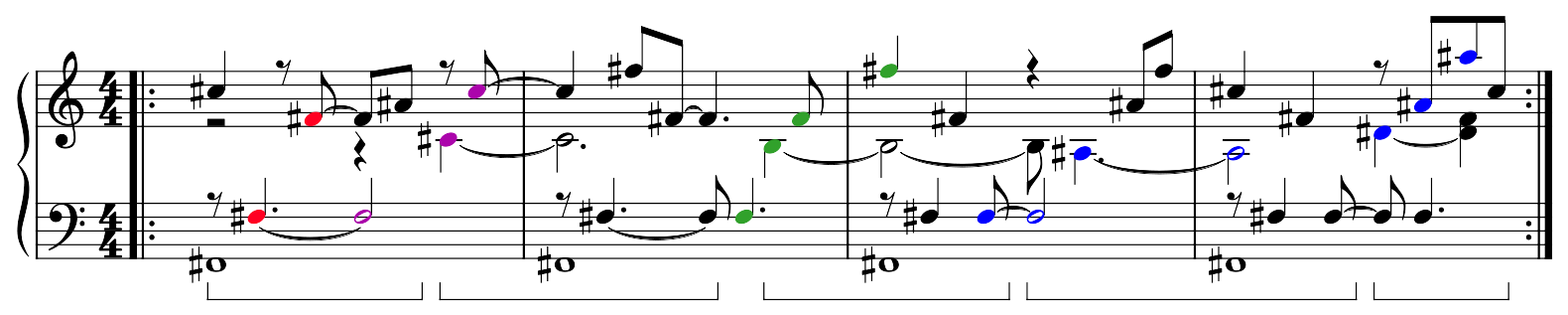

We can do the same thing for the rows:

Traversing the overtone grid by rows

These are represented as patterns here:

Notes corresponding to the rows of the overtone grid

And finally for the diagonals:

Traversing the overtone grid by diagonals

We see the patterns here:

Notes corresponding to the diagonals of the overtone grid

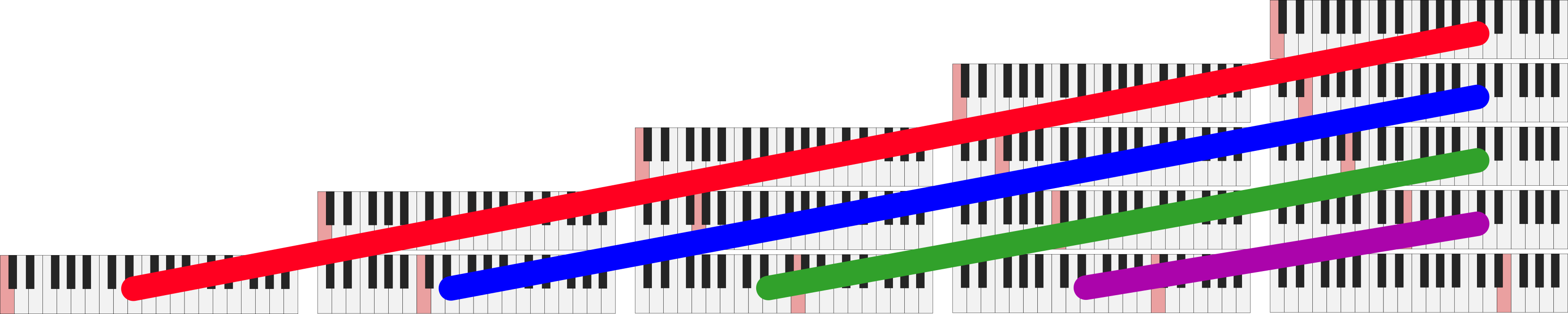

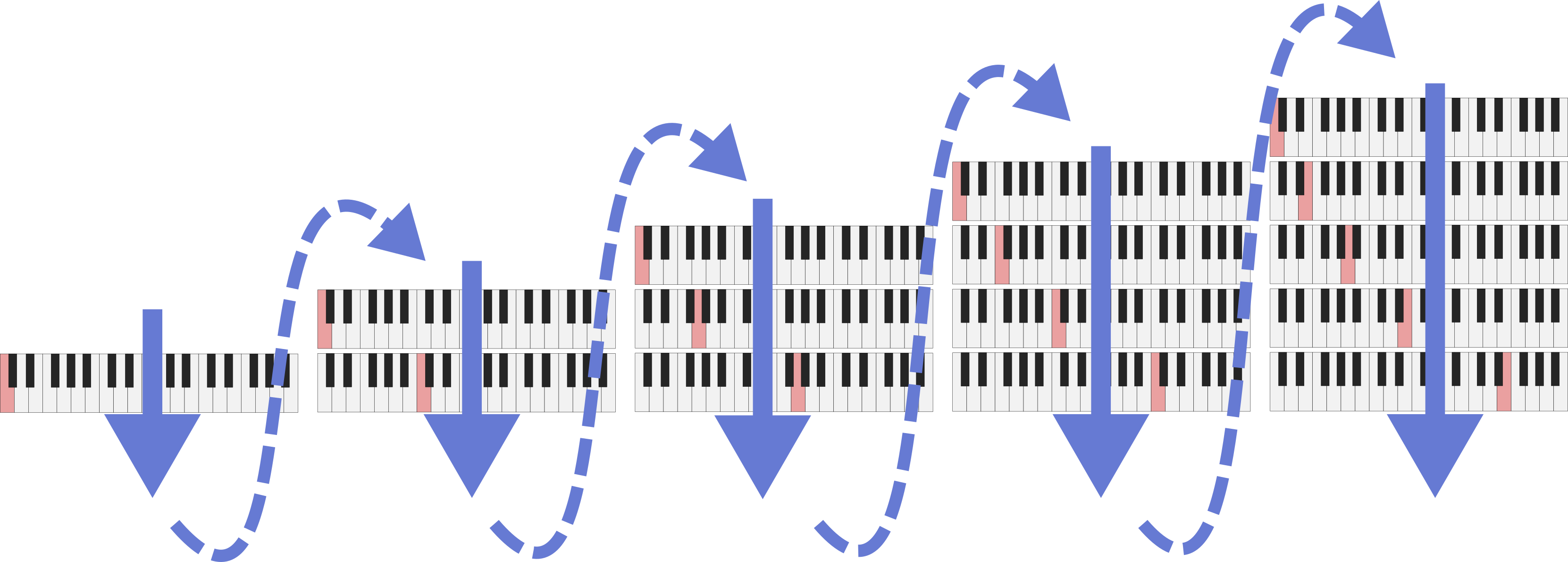

We add in notes to the piece in an order determined by flattening the grid. We traverse the columns from left to right, ignoring duplicate notes, as follows:

Procedure for flattening the overtone grid

Notes are introduced in this order. While there many repeated notes, there are 10 unique notes. We can see the introduction of each new note by looking at the score where the new note introductions are highlighted:

Highlighted positions indicate where a new note in the flattened overtone grid is introduced in the score.

We also can hear each new note in the recording, see a new unique set of stripes show up in the spectrogram of the recording when a new note is introduced.

So, the structure is made up of a flattened version of the overtone grid, and the notes come from patterns obtained by traversing the grid in different directions.

Appendix: Patterns on the grid

There are several patterns to the overtone grid. First, notice that the bottom row is the overtone series. This is because the bottom row is where \(M=1\), so \(M/N\) is the same as \(1/N\).

But interestingly, the second row from the bottom also appears to form an overtone series, but missing the first note. If we try to extrapolate it out, we see that it would be exactly one octave lower. Mathematically, this is because if we replace \(L\) with \((2L)\) (i.e., the string length for the tone one octave lower), then \((2L)/1\), \((2L)/2\), \((2L)/3\), and so on is just the overtone series for a string of length \(2L\)!

This same trend continues as we go to higher rows. In the third row from the bottom, we have the top of an overtone series which starts on the low F, corresponding to a string of length \(3L\). It becomes more difficult to notice after the third row, but the trend still continues. This row structure comes directly from the mathematical definition of the overtone series.

The columns are even more interesting, giving rise to a reverse of the overtone series, the “undertone series”. In the normal overtone series, we start with the fundamental frequency, and then go up an octave, and then a perfect 5th, then a perfect 4th, then a major 3rd, and so on. In the columns, we do the opposite. Our “pseudo-fundamental” frequency occurs on a high note at the bottom of the column. As we travel upwards in the grid, we first go down an octave, and then down a perfect 5th, then down a perfect 4th, then a major 3rd, and so on.

There is also an interesting pattern in the diagonals. Along each diagonal, the pitch gets closer and closer to the fundamental frequency at different speeds. The main diagonal corresponds to the case where \(M=N\), and thus, \(M/N=1\), so this will always be the value of the fundamental frequency. But what about the off-diagonals? The first diagonal is defined as the combinations of \(M\) and \(N\) such that \(M-N=1\). So then, we have \(L\times 2/3\), \(L\times 3/4\), \(L\times 4/5\), and so on. As the value of \(N\) gets larger, we will get closer and closer to the fundamental frequency.

Acknowledgement

Music of the Leaves was based on a conversation 10+ years ago with my former research advisor Clarence Lehman. Thank you to Chiara Naldi for recording Music of the Leaves and including it in her concert series.